We all know Montessori classrooms differ vastly from their more conventional, traditional counterparts, and views on how children developmentally react to fantasy and reality are one of the key components of those differences.

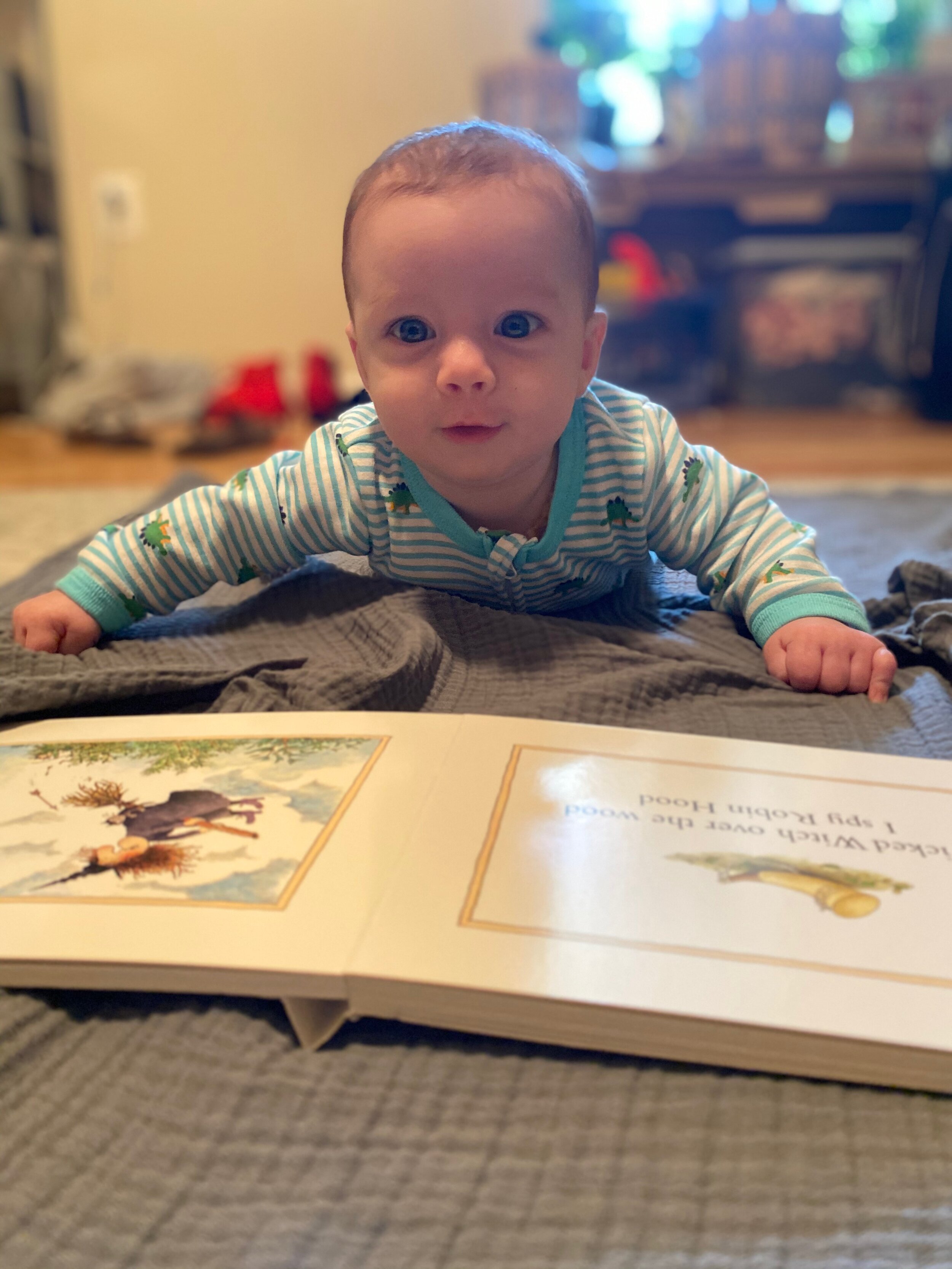

You may or may not already know, but Montessori schools discourage the introduction of fantasy to young children (children under the ages of 5 or 6). This means we do not use play kitchens, have a dress-up area in the classroom, or rely on books with dragons and fairies. This often evokes a visceral reaction from those new to the approach, but after learning the scientific reasoning it makes much more sense.

Some people hold a misconception about Montessori regarding their assumption that the method stifles imagination and creativity. The is unequivocally false. We wonder if this misconception stems from tangled definitions of fantasy and imagination, which are two very separate concepts. Fantasy is the stories and ideas drawn from a world which does not exist (those fairies, dragons, talking horses, etc.). Imagination is the ability to conjure images or scenarios in one’s own mind, separate from present sensorial input.

So, what is the difference, really?

Fantasy is giving wooden fruit to play with instead of a real banana to slice. Fantasy is reading a book about a talking dog rather than reading a book about the different breeds of dogs around the world.

Imagination is a child on the playground pretending they are an eagle because they saw a live one for the first time that weekend. Imagination is children playing ‘family’ because they are driven to practice the roles that are modeled for them in their own homes.

Imagination is inherent in the human mind. It’s where our creativity comes from, and it’s one of the ways we process learning about the amazing world around us. As Montessorians, we revel in the magic of imagination (and, as children get a bit older, we use it to our advantage, but more on that later).

As Montessorians, we recognize that young children have a difficult time distinguishing the differences between reality and fantasy, and that blending the two within their experience can be confusing. We also know, from Dr. Montessori’s own observations, that young children typically prefer reality to fantasy. For example, in her first classroom, she had a dollhouse and read folktales. Children were far more interested in leaving those activities behind to observe an earthworm or serve tea to visitors.

Our perspective asserts that in a young child’s life, everything they encounter is awe-inspiring and fills them with wonder. We need not tell them tales of unicorns, in part because they often have a hard time distinguishing between whether they are real or not, but also because an actual horse is just as fantastic to them. When the whole world is still relatively brand-new, animals, plants, the environment, and real people provide more than enough inspiration for their young minds.

We all know that even very young children utilize their imaginations (as we mentioned several examples above). This is a normal and natural part of development which we value and honor. We would just rather give our students real, authentic opportunities as opposed to presenting them with fake ones. We know that a three-year-old is fully capable of learning basic food preparation skills, so we guide them and leave them with a sense of empowerment. Even a toddler is old enough to begin learning how to sweep up a mess on the floor. Rather than supplying a toy cleaning set, we make available real cleaning tools that are appropriately sized, and we guide young children as they learn to use them effectively.

Once children enter the second plane of development, around age 6, our approach shifts. We know children are more able to differentiate between reality and fantasy, so we don’t discourage fantasy books (although we do provide plenty of nonfiction). We also know that children at this age, through about age 12, are highly motivated to learn through the use of their imaginations.

While we still do not rely on fantasy to drive our teaching, we do lean heavily on imagination for older children. Several of our most important, foundational lessons about the universe, life on Earth, and humanity itself are delivered with the use of storytelling. The stories we tell are true, but we allow children to mentally picture themselves in historically critical moments. Elementary-aged children are seeking to find their own place in the universe, and their developed sense of imagination helps take them there.

So, what are the practical implications of these principles in regards to parenting? We would say give your young children the gift of reality! Give them opportunities to use real tools, to go outside and observe and discuss real things. The younger the child is, the closer to reality everything that you present to them should be.