We in the elementary faculty have been as busy as the students! While they have been either getting going with animal research or learning vocabulary associated with the skeletal system, we have been engaged in lots of first and secondhand professional development, as well as preparing for our fall conferences. What do I mean by secondhand professional development? Mrs. Dankoski just returned from a conference which gathered some of the finest minds in Catholic Montessori. She brought home lots of ideas and resources about how to help today's children. Similarly, our very own Mrs. Mello has been enjoying two night classes on elementary education in a Montessori environment. I've loved the insight I have received from them. While I have only been a teacher for ten years, we are living through a rapid time of change. I am blessed to be part of a school so committed to improvement and sharing. In this busy, busy time of year, I almost decided to write my update a day late, until I remembered what the subject matter was that I would be writing about.

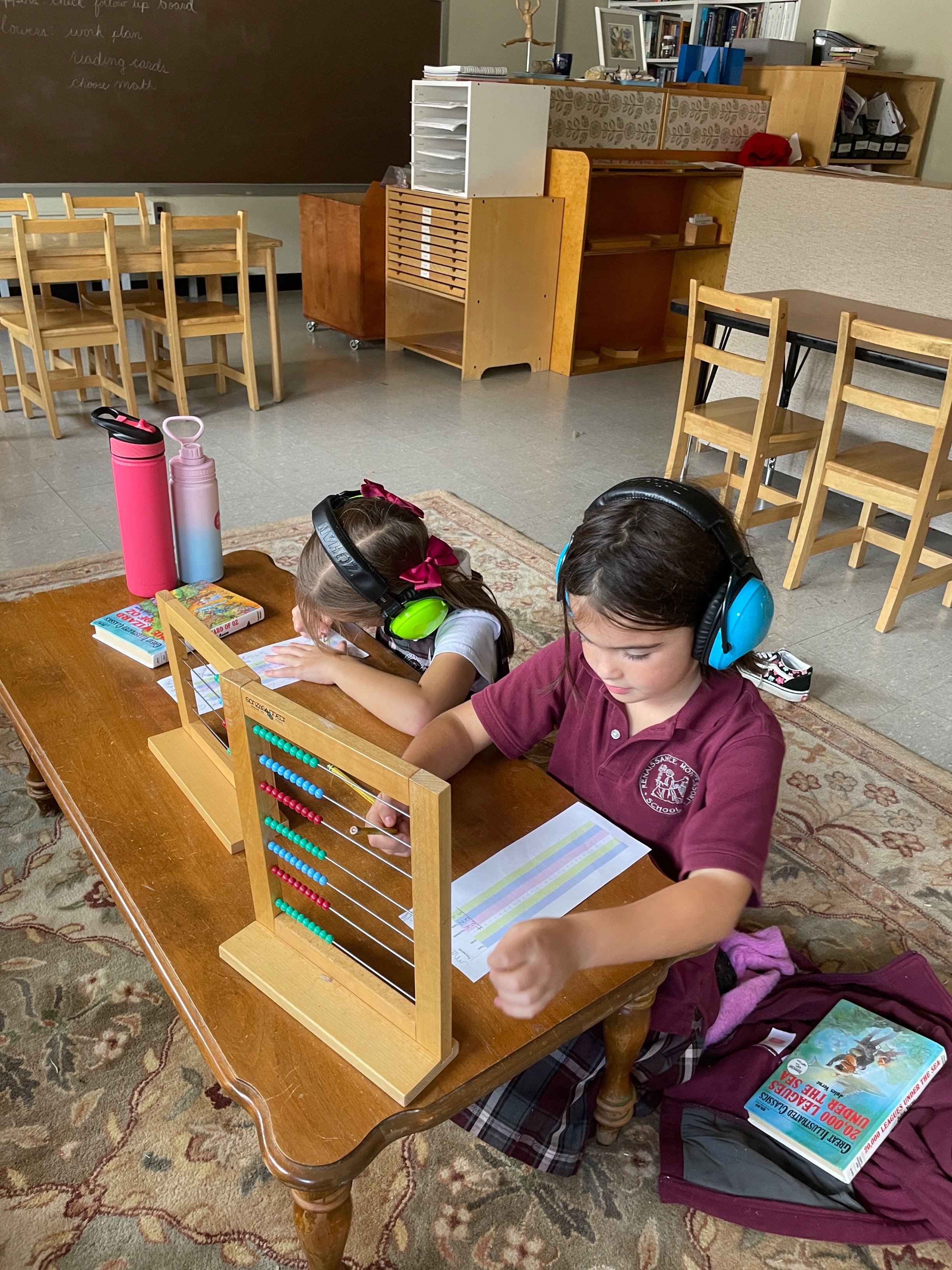

The thing I'd decided to write about today is tenacity. It is a noun that brings up images of sweaty men clenching teeth. Perhaps you prefer words like "persistence", "determination", or "perseverance", but however you say it, this is a virtue we ought to instill in the children of our school. Your child will be in elementary for a long time. In my experience, over that long six years, tenacity will take a child much further than ability. Tenacity will make a child practice seven problems instead of five today. It will make them want to get them right. It will make them passionate about improving.

I can understand if you want to say, "yes Mr. Short, but if doing those two extra problems is so transformative, why don't you just make everyone do the two extra problems?" All I can say is that the source of the desire to complete those two problems matters. A teacher will not always be there to force a child to do that little bit extra. Eventually the desire and initiative must come from within.

One way you can cultivate this at home is to find out what your family's version is of what I might call a "morality theater." For my family growing up in New England, it was hockey. Whether we were watching a college game in a half empty college barn that always smelled a bit like exhaust fumes or watching professional hockey from the comfort of our sofa at home, my dad always involved us in a verbal analysis of what was going on. Some was what you might call the "x's and o's" of the game, but much of it was about the dichotomy he set up for us between effort and talent. He pointed out how often the players who were all talent and no effort would fail in their defensive responsibilities. He thrilled us with descriptions of the games of bygone days--ones that had decided seasons, ones that had crowned heroes. It was not lost on me how often these heroes were not the expected stars of great talent, who had been groomed for this moment from childhood. Often these were the exact players who seemed invisible in the moment of decision. More often than not, the heroes were the ones we called "lunch pail" players. There were many ways that my parents taught me that hard work is what counts, but giving me role models to emulate was exactly what I needed as an elementary aged student.

While my parents were completely unfamiliar with Montessori principles, they hit the nail on the head here. The second plane child needs heroes and role models. Don't let the world give them to your child--you might find that their heroes are immoral, or, even worse, a Youtuber! Find your own "morality theater" where you and your child can safely discuss ethical decisions and cultivate virtue. Perhaps it will be watching football together. Perhaps it will be discussing figures of history or characters of literature.

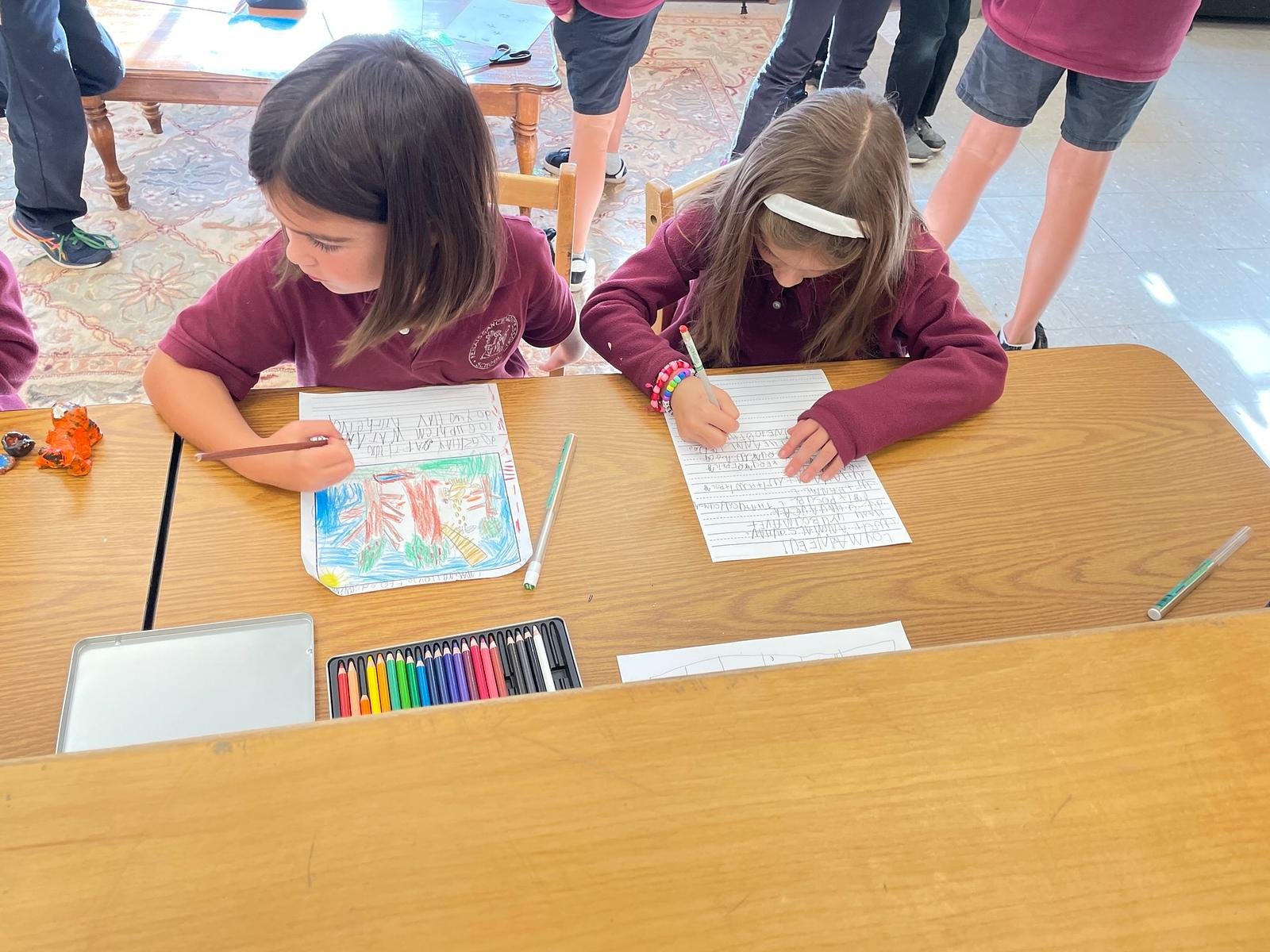

One thing we are doing at RMS to introduce your child to role models of virtue is preparing for our Living Souls Museum. The children have been loving their preparation for it. I must admit that for a brief moment as I watched the children work on their reports today, I asked God if this was the entire reason RMS exists, so we can do this together. Perhaps so. In the choices of these children I see many saints of great love, and others of great tenacity. I am thinking particularly of Saint Paul, and the many other martyrs represented in our class. There is a sort of love present in this tenacity; a refusal to be denied union with what we love. May we feel that way about learning; may we feel that way about the Lord.

Some of you may know that my wife is an occasional extracurricular guest in the classroom. Over the summer she used her designer's eye to help Mrs. Dankoski choose some new furniture and art. She is also our link to veterinary advice, thanks to her contacts at the Roger Williams Park Zoo in Rhode Island. (It was through these channels that we got the advice to handle the bearded dragon's mouth rot. You will be happy to know that our lizard is fully healed!) During the school year she makes appearances to lead large group art projects, or special small group projects. Last year on Candlemas she led us through a wonderful candle dipping project. In the spring she planted a bunch of dye flowers near the chicken coop. Last month the upper elementary was able to hammer these flowers into some white socks, to make dye flower patterns onto them. It was not until last Friday that she was able to make it back to do a flower craft with our lower elementary students.

As I pulled up to the school, I did not think the project would work out. Frost covered the grass. Surely the flowers had been ruined. I sent her a mopey text that the time had come and gone and we had missed it. In what I can only describe as a beautiful act of God's providential love, somehow the frost had killed all the flowers except the dye flowers. With some fourth year girls there to help supervise, the younger students came out in groups to hammer flowers onto paper. These pieces of paper have been drying out on the window sill for almost a week now. Today, I think, we will brush off the crumbly remnants of petal and calyx and admire the flower art that remains on the paper.

In chapter six of Jeremiah's book of prophecy, he famously counsels us to take the old paths. There is no older road than living in contact with our place and with our land. There is something special in the way we use our land here at RMS. May we grip tenaciously to our community and our faith, and may we find that like trees and their roots, that which feeds us is also what keeps us upright.