The Young Children’s House continues its wonderful journey of growth and learning with the children. I want to reflect on one of the central principles of Montessori education – INDEPENDENCE. This concept is at the heart of everything we do in the classroom, and it extends far beyond simply encouraging children to complete tasks by themselves. Independence is about empowering children to be confident, self-sufficient individuals who can navigate their world with competence and self-assurance. Montessori saw independence as both a physical and psychological achievement, a process that unfolds gradually as the child grows, learns, and refines their abilities.

In our toddler environment, this drive for independence is evident in nearly everything the child does. Their mantra, although unspoken, is clear – “Help me to do it myself.” Every day, we see children eagerly working toward mastering tasks on their own. You might have noticed this from the photos we share with you on Transparent Classroom, pictures of your child engaged in familiar activities, perhaps sitting in a chair, pouring water from a pitcher, doing a puzzle, window washing, riding the trike, climbing up and down the stairs, washing hands, pushing/pulling objects, or polishing an object. You may wonder why we capture similar moments repeatedly, but there’s a reason for it – your child is working hard to master these skills, and repetition is key to that mastery. These are necessary steps in their journey towards independence. Children achieve independence through continuous activity. It’s not something that happens overnight, but rather through constant effort, practice, and repetition. With each task they take on they are building essential skills. Independence is not a destination but a journey that evolves over time, and this journey is supported by several key elements within the Montessori environment.

One of the most fundamental components in supporting independence is appropriate clothing. Children need to wear clothing that allows them to move freely and comfortably as they learn to dress and undress themselves. In the classroom, we offer dressing frames that allow children to practice essential skills like fastening buttons, zippers, Velcro, snaps, and buckles. These small, practical tasks develop fine motor skills and help children take responsibility for their own clothing, an important step toward becoming more self-reliant. The ability to dress independently is more than just a skill, it’s a confidence booster that shows children that they are capable of taking care of themselves.

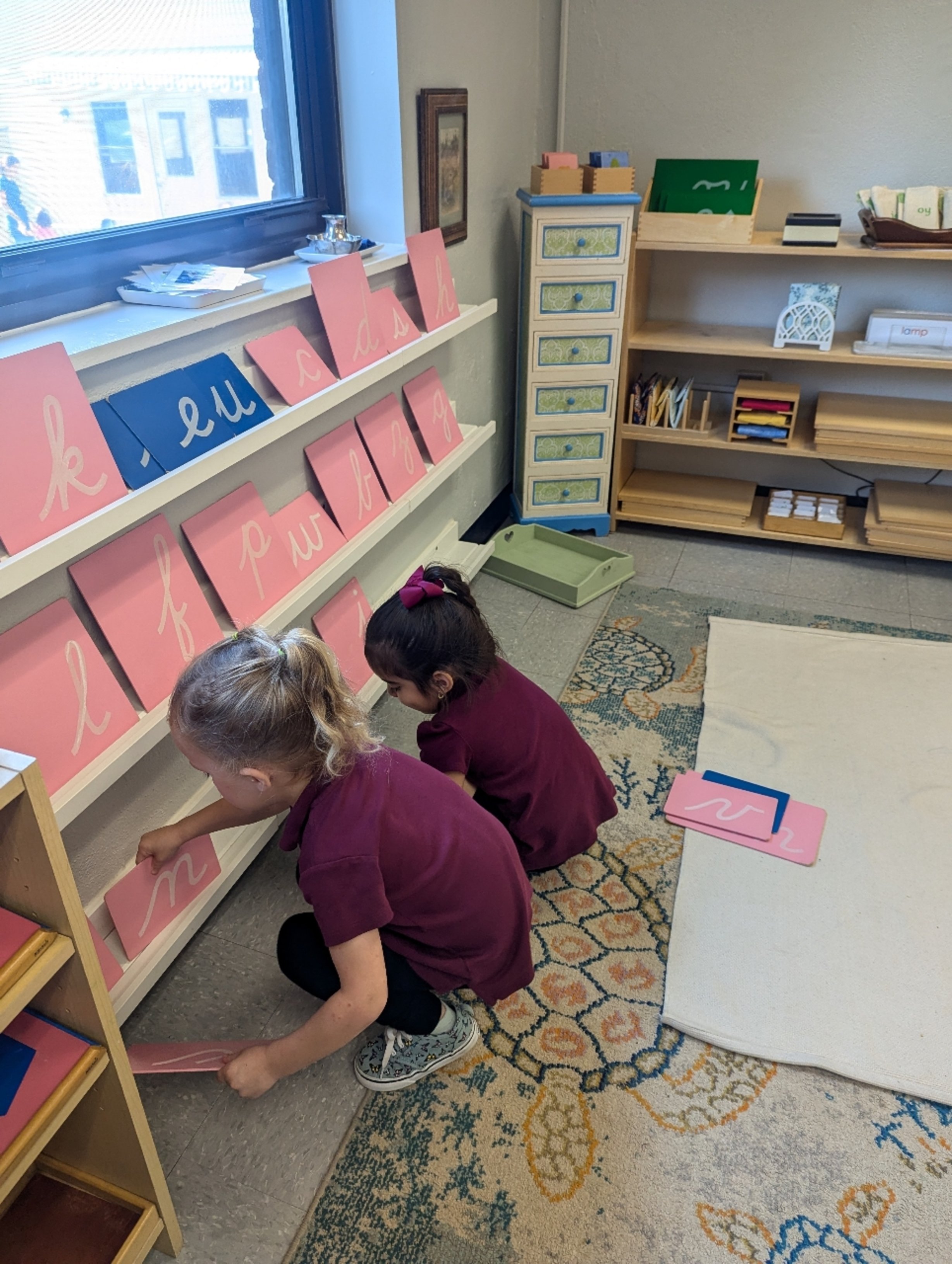

The Montessori classroom, the prepared environment, is carefully designed to support a child’s quest for independence. Everything is thoughtfully arranged to be accessible and inviting to your child. From child-sized furniture to low shelves with easily reachable materials, the space is designed so that the child can explore and engage without the constant need for adult assistance. This helps the child feel empowered – they can choose what they want to work on, select the materials they need, and return them to their proper place afterward. In doing so, they’re learning responsibility, order, and how to take control of their own learning experience.

Another essential aspect of fostering independence is freedom of movement. In the Montessori classroom, children are not confined to specific tasks or areas for set periods of time. They are given the freedom to move about the space, choosing activities that interest them and working on them for as long as they wish. This freedom allows them to develop both physically and mentally. For instance, walking up and down stairs builds strength, coordination, and confidence, while the simple act of sitting on a chair teaches balance and control. As children engage in pushing or pulling objects around the classroom, they learn how to navigate their environment with care and purpose.

Independence also involves mastering practical life skills, which are a core part of the Montessori curriculum. Practical life activities, such as sweeping the floor, food preparation, or polishing an object, provide children with opportunities to practice real-life tasks in a meaningful context. These activities are not only valuable for developing coordination and focus but also for building confidence. When children complete a practical task, they gain a sense of accomplishment, knowing that they are contributing to their environment and taking responsibility for their actions. These tasks are designed to be self-correcting, allowing children to learn from their own mistakes without needing constant adult intervention.

Repetition plays a huge role in the young children’s development. When children choose to repeat the same activity over and over again, they are working toward mastery. This might be why you see some pictures of your child engaged in the same tasks day after day. Each time they repeat a task, they are refining their movements, increasing their focus, and developing their confidence. Mastery comes from this process, and it’s through repetition that the child solidifies their independence.

Adults play a significant role in the child’s journey toward independence, though it might not always be the role we expect. Often, the adult can be the obstacle, standing between a child and their independent growth. It’s tempting to step in and help when we see them struggling, but in Montessori, we recognize the importance of allowing children to work through challenges. By stepping back and giving them the time and space they need to figure things out, we foster resilience and problem-solving skills.

The adult’s role in the Montessori classroom is to prepare and maintain an environment that supports the child’s self-directed learning. We carefully select materials, arrange the space, and demonstrate how to use materials and engage in daily activities. We model behaviors and activities, not by doing the work for them, but by showing them how it’s done and then allowing them the freedom to practice and explore on their own. Additionally, we strive to protect your child’s concentration, minimizing interruptions and ensuring they have the time to focus deeply on their work.

In this process, language plays an important role. By communicating clearly and respectfully, we empower children to express their needs and make choices. We tailor our support to meet each child’s unique developmental stage, offering the right balance of guidance and freedom. In this way, we ensure the child feels both supported and capable of taking on the challenges that come with growing and gaining independence. Through thoughtful preparation, careful observation, and an understanding of each child’s developmental needs, we create an environment where children feel confident in their abilities to care for themselves, their surroundings, and one another. It’s such a joy to watch this process unfold in the classroom, and we are grateful to be part of your child’s journey.