I have been badly neglectful by hardly mentioning our atrium in our first month of weekly updates. In case you are new to our school community, you might not know much about what an "atrium" is and what happens there. Let me break it down.

First of all, a Catholic Montessori school such as ours is not simply a Montessori school with some faith sprinkles dusted on. Rather, it is the vision of Maria herself fully realized. One of the tiny tragedies in the great mosaic of 20th century carnage in the years between 1914 to 1945 is that almost as soon as Maria Montessori set up her full educational vision in Barcelona--schools with primary and elementary classrooms and a fully integrated academic and spiritual program--she had to flee the unrest that would culminate in the Spanish Civil War. The case can be made that she never had a home again. She ended her life traveling around training teachers and addressing audiences about how a sea change had to occur in education and childrearing if we were ever to live in a society free of war and genocide. Away from classrooms of her own, it would be left to her successors to flesh out her ideas about the education of the elementary child and the religious formation of children. Her son Mario carried on her mission of training teachers and designed many new materials for the elementary aged child, based on his mother's writings collected in Spontaneous Activity in Education and The Advanced Montessori Method.

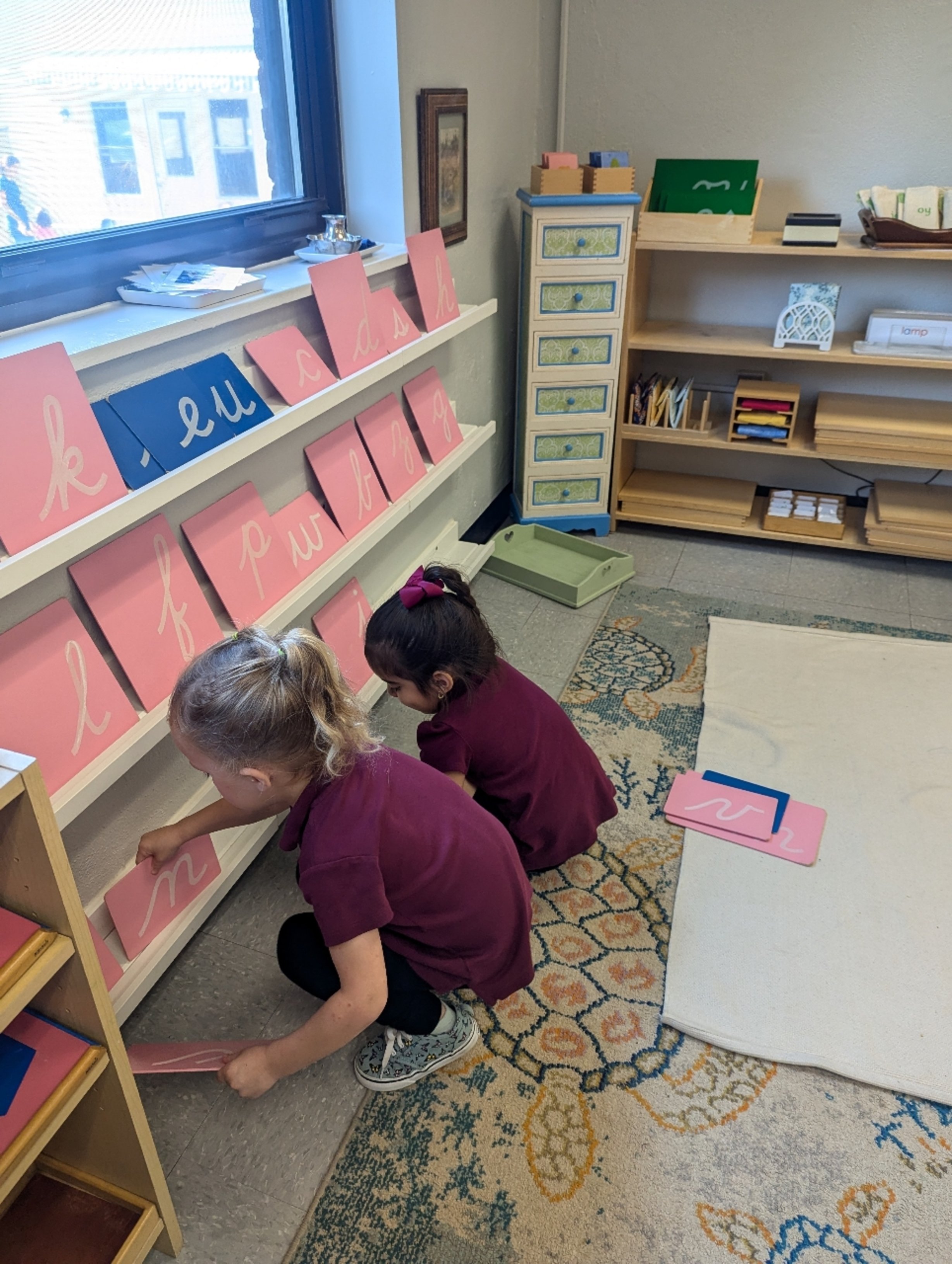

In much the same way, Montessori left us with her thoughts on religious instruction collected in The Child in the Church and On Religious Education, as well as a slim volume on orienting children to the Mass. Beginning in 1954, the Italian scripture scholar Sofia Cavalletti and the Montessorian Gianna Gobbi took up the mantle and put in decades of tinkering with the materials designed by Montessori, inventing new ones, and, most importantly, observing children working in the classroom. Visualizing these classrooms as the entryway into the Church, they began calling each one an atrium. Like our academic areas, each is a prepared environment designed for the child's independent use and exploration. Their pedagogy, as you know, is entitled The Catechesis of the Good Shepherd.

In the primary classrooms, the atrium is an area of the classroom. This illustrates to me an important reality: that to our school, the spiritual formation of the child is a subject as important as math or language. Looking at it another way, the atrium works are the connective tissue of the whole body. They are foundational. Looking at it yet another way, the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd is the soul of our school; the essential part, the life principle. I think it significant that some members of our wider community come to our property on Fitzwater Drive to visit an atrium, but not a single one comes for the academic subjects to the exclusion of catechesis. We are not the kind of Catholic school to demand your child wear a plaid skirt, pray before lunch, and pat ourselves on the back as if that was the summation of the faith. It is in our bones, the substance of our roots. It is by being truly ourselves that we can be truly welcoming of the beloved members of our community who share our mission, but not our Catholic Christian religion.

When I first read Sofia Cavalletti's books over the course of the winter of 2015 I was struck by how many photos of student art she included. Befitting the Montessori cliche of "process, not product", the work was not chosen because it was beautiful exactly, but because it was a window into the child's prayer. Included in the accompanying photos today are three works of art by children made in the atrium in the past week. Two are by upper elementary students in reaction to meditation on the parousia, when God is "all in all". They had been discussing with our catechist, Mrs. de Bernardo about the beauty we will witness at that time beyond time. Colors we have never dreamed of will be visible. And in the center of each picture is the Lord, appearing to our hunger and thirst as Eucharistic bread and wine.

Now take a moment to look at our other piece of art, created by a boy in his second year of elementary study. This work was done following up a presentation with La Fettuccia. This work, named after the Italian word for "ribbon" is an immensely long fabric timeline which runs from creation to parousia. It is a chance to experience a God's-eye-view of the grand swath of the universe's history. Children meditate on the three grand moments of this history: creation, redemption, and parousia. God created this universe in love. In His great act of love, He freed us. At the end of time He will come again and God will be all in all. In the atrium, a child's work is his prayer and his prayer is his work.

Let us dive into this young man's prayer. Let me be clear, that this will be a sort of meditation on a meditation. Neither Mrs. de Bernardo nor I have gone in depth with this child into what he was thinking when he drew this or that detail. We certainly will do that sometimes, but this has been a busy week and we did not get to it. An older edition of Gianna Gobbi's book is entitled Listening to God with Children. I offer this meditation in that spirit.

In the photo of his work you probably will find your eye drawn first to three crosses. Crosses are a major motif in this child's work. This time the cross is presented as it appears on our atrium timelines as a symbol of the parousia--a cross superimposed on the globe. There are three. What could it mean? Are they the three crosses of calvary, somehow each transfigured, in a sense, by the Lord's triumph? It would be saying too much to assume this student means anything at all about the ultimate fate of the two bandits crucified with Christ, but Mrs. de Bernardo and I both found ourselves thinking of this as we discussed the fruit of this student's contemplation. Perhaps his mind was more on those three moments of the sequence which is a touchstone of so much of the lower elementary student's atrium work: creation-redemption-parousia. I found myself remembering how the mystics have sometimes described the whole of the new creation as being ablaze with God Himself, just as the burning bush was when God told Moses to take his sandals off and revealed to him His unpronounceable name. And what of the cross of the redemption presented in the light of parousia? God's triumphant work on the cross will never be superseded. The Lamb who will be the light of the New Jerusalem is still the Lamb "slain from the foundation of the world". I need to be constantly reminded that it was by His wounds that the disciples recognized the risen Lord.

Below on the left stands the Good Shepherd standing in triumph, holding his sheep aloft. Both are in the rapture of joy. One thing I would like to point out, is that this boy took a familiar image--that of the Good Shepherd--and manipulated it to his needs, changing their postures and facial expressions. In the center is Jesus walking on water. To the right of him is a lamb marked as "a 100 lamb". By this does he mean the hundredth lamb, the one for whom He left the 99? I could meditate the rest of my life on the image of Christ walking on water to save that lost lamb. Christ did the impossible to save us. Every moment of His earthly life, each teaching, each nature miracle, each healing was a loving act to go out into the wilderness to find the sheep that was lost.

I suppose you could say that I am overloading the art of a seven year old with all sorts of dubious significance and airy fairy nonsense. With my rational adult mind I am eager to make all sorts of connections using this boy's work. But do not say that I am giving it more meaning than he intended. This work was his prayer, his worship. I would argue that there is infinite meaning in this picture. Some he intended with his rational mind. Some I recognized with mine. Some of the depth of content is only known to the Spirit, which intercedes by inexpressible groanings, and sometimes with colored pencils.