“To be able to observe, the human’s mind must be clear, the soul must be open, and the body must be willing.” (Maria Teresa “Chacha” Vidales)

In Montessori, you'll frequently hear about the importance of the adult observing. But what exactly does observation mean in its truest sense?

Observation is an art that allows us to continuously evolve, shaping our perception of the world and our place within it. It goes beyond simply seeing – it's an active, engaged process that leads to meaningful outcomes. Unlike sight, which can be influenced by preconceived notions, genuine observation is anchored in the present moment. As life is in a constant state of change, observation helps us appreciate the ever-evolving nature of existence.

When we observe without bias, we open ourselves to seeing the world through the eyes of others, particularly the child, who reveals the intricate paths of their development. Each moment becomes a fresh opportunity to perceive the essence of the child anew. Our dedication to observation is a gift to the child and a reflection of our own journey toward self-awareness and growth.

Becoming a skilled observer takes consistent effort, repetition, and practice – it’s a lifelong process that requires us to step out of our comfort zones and embrace the dynamic nature of reality. To observe fully, we must quiet our minds, allowing our authentic selves to connect with the present moment.

To become an adept observer, the inner preparation of the adult is needed. Inner preparation of the adult involves more than just having tools or focus; it requires an internal readiness to truly perceive what is in front of us. While setting up the physical environment is straightforward, preparing ourselves mentally and emotionally takes more effort. This internal work is essential, as we must be fully present, both mentally and physically, to establish a meaningful connection between the child and the environment.

We cannot offer what we do not possess. Understanding and fulfilling our own needs allows us to better support the child. By practicing observation and setting aside biases, we enable the child to develop independently. Observation helps us recognize the child’s evolving developmental path and adapt our guidance accordingly.

Our role is to observe deeply and quietly, remaining fully present with the child and creating a nurturing environment. Humility is key – observation fosters our own growth and strengthens our connection with the child. Keeping an observation journal helps build this skill through practice.

We must also embrace our own growth, letting go of past mistakes, and understanding that perfection is not the goal. The aim is to continually improve and restore our innate capacity for observation, which modern life often diminishes. In doing so, we foster deeper connections with the child and the world around us. Patience and grace are essential. The child seeks not a perfect adult but one who is striving to offer their best.

With that being said, observation is one of the most important works of the adult. It allows us to fully understand and perceive the child. There are three types of observation:

Self-observation: By turning our attention inward, we improve our ability to observe others effectively. Keeping a journal can be a valuable tool for articulating our thoughts and clearing biases. This practice helps us move forward without the burden of self-criticism or preconceived notions. Just as we observe children with openness and clarity, we must apply the same scrutiny to ourselves, examining who we are and our role in life.

Observing children (Direct): We should aim to be unnoticed, remaining quiet and still to avoid drawing the child's attention. Avoiding direct eye contact helps maintain the child's focus. Simple outfits, free of flashy accessories or jewelry, minimize distractions. Deliberate and mindful movement is also essential. Staying fully alert during observation is key. Focus solely on what is in front of you and record observations by hand, without rewriting, to capture the essence of the moment.

Interacting observations (Indirect): Observing while actively working requires practice. This challenge is particularly strong at the start of the year, when children are still adjusting to the environment. Mario Montessori emphasized the teacher's "sixth sense" for knowing what happens behind their back, highlighting the importance of observing even while engaged in other tasks. Record-keeping is important for tracking observations over time, as it provides insights into the children’s progress and needs, especially when it’s easier to observe the materials than the children directly.

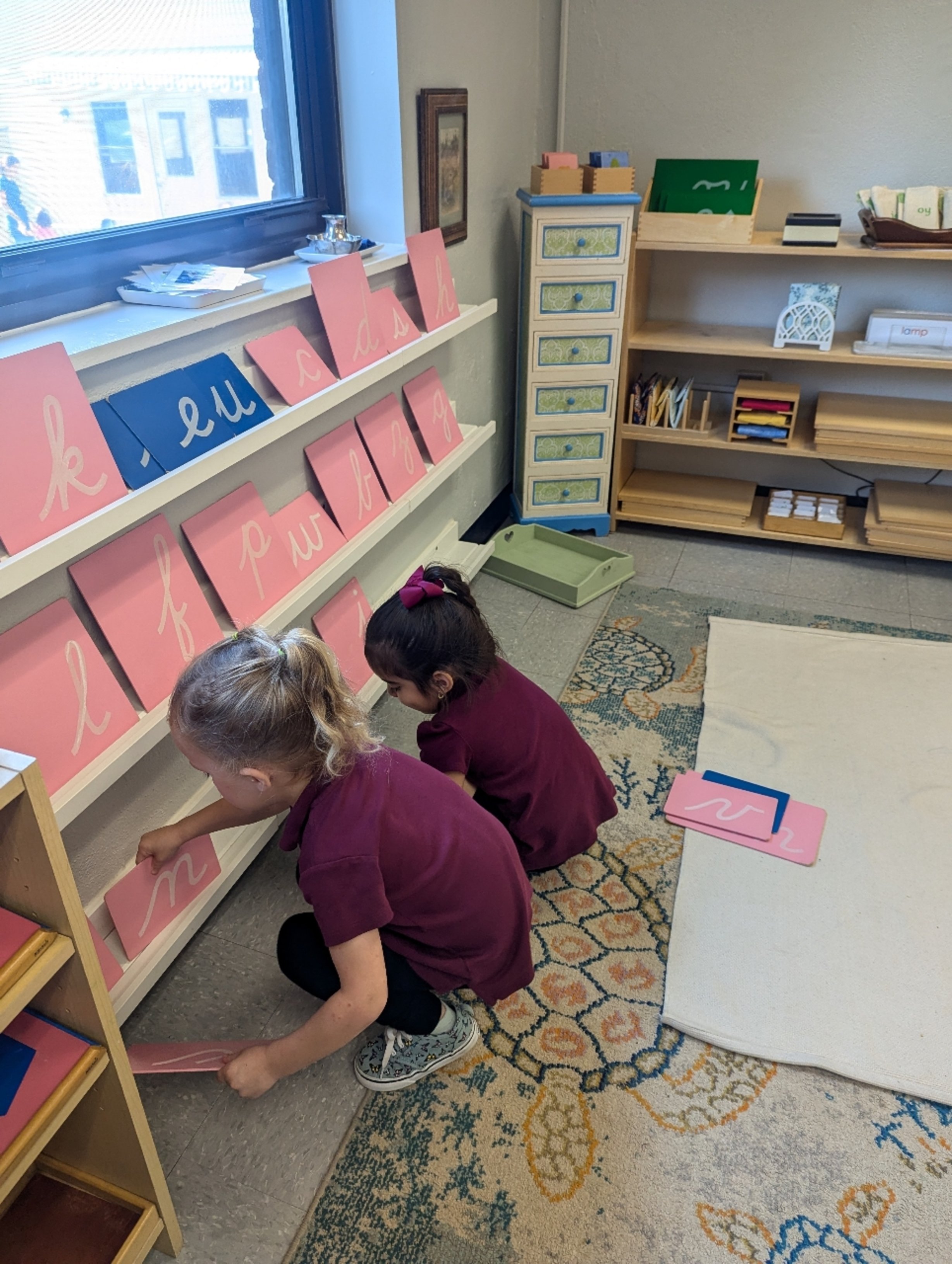

In the Young Children’s House, it is essential that all adults in the environment are actively observing, especially during the early days of the school year when the children are still adjusting to their surroundings. I recently had the privilege of sitting down for a direct observation (being a "fly on the wall"), allowing me to witness the magic of real time development. Although the children had only been in school for a month, I was captivated by their ability to show concentration, empathy, and growth – so much happening in such a short time for children aged 16 months to 2 ½ years.

One moment that deeply touched me was when I saw a child retrieve a tissue. He carefully walked across the room, and I watched, wondering what his intent was. He approached another child, who was busy climbing up and down the stairs, and who had mucus running from her nose. He seemed unsure whether to hand her the tissue or perhaps wipe her nose himself, but after some deliberation, he went to an adult for assistance, signaling his desire to help his friend. This small, yet profound act of empathy reminded me of how important it is to observe without preconceived notions. Had I approached the situation with assumptions, I might have thought the tissue was for himself or worried that he was going to make a mess. But by staying present and open, I was able to witness his thoughtfulness unfold naturally.